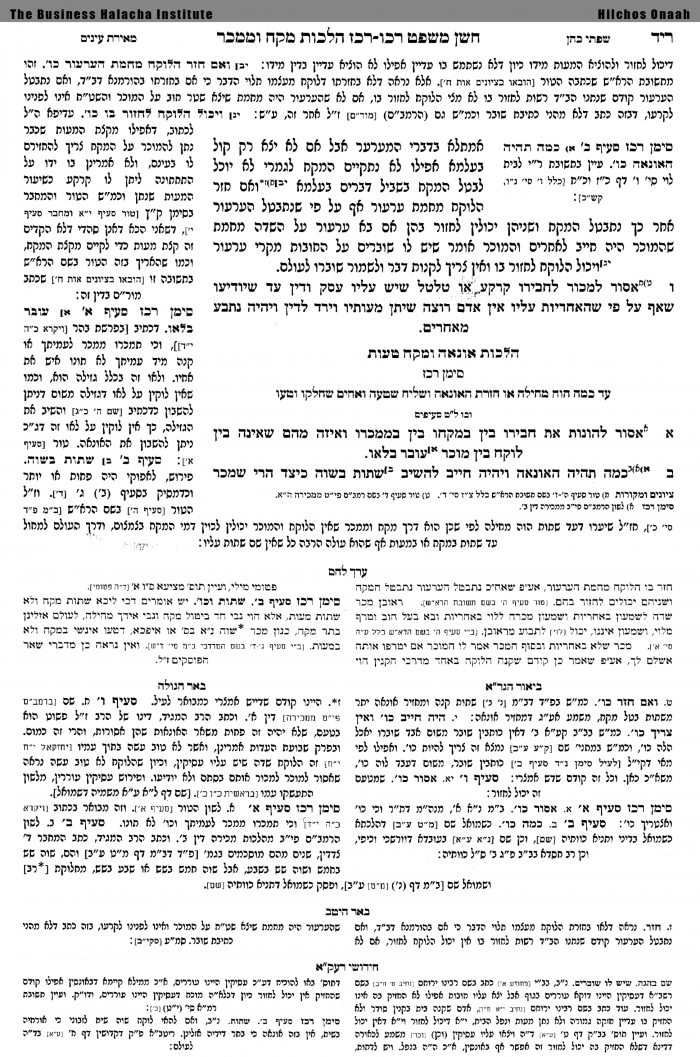

Shulchan Aruch

Overcharging an unsuspecting buyer or underpaying a naïve seller violates the biblical prohibition of Ona’ah. A unique aspect of this prohibition is that although both parties willingly agreed to the price and neither party was coerced or mislead in any way, nevertheless, if the buyer is unknowingly paying above its market value, the seller violates Ona’ah. This applies even if the buyer initiated the deal- he unilaterally offered the seller an above-market price for the product without any solicitation. Simply accepting an offer that is inconsistent with market value is prohibited, unless the counterparty was notified of its true value and consciously agrees to overpay/undercharge. (See Sif 21 for the correct formula to waive Ona’ah)

Think about it: Ona’ah applies both to the buyer and seller. Although we typically think that sellers take advantage of unsuspecting buyers, the reverse can be true as well. If a seller does not realize the value of what he has, a buyer that underpays will violate the prohibition of Ona’ah.

Of note is that Halacha does not attempt to set market prices. These are determined by free-market forces, government regulation, or by some combination of the two. Regardless of how prices are set, Ona’ah precludes a person from taking unfair advantage of a counterparty’s unfamiliarity with the market norms. See section “Market Price” for a discussion of the factors that are taken into account to determine pricing.

Think about it- while in civil law the rule of caveat emptor means that each person looks out for his own interests, Halacha has a diametrically different approach. Each person bears responsibility to ensure that he is not taking unfair advantage of his counterparty’s mistake or lack of knowledge.

Another critical point is that Ona’ah has nothing to do with profit margins. It is completely permitted for a merchant who manufactures items cheaply to mark up his goods as much as he pleases, provided the final sales price is consistent with market value. Conversely, a merchant that overpays for his merchandise may not overcharge his customers, and will be forced to suffer a loss.

Think about it: By definition, an item that has no market price cannot violate Ona’ah. Therefore, an inventor is free to set any price he chooses for a new item for which a market does not exist.

Think about it: The Ritvah (Kiddushin 8a) introduces a concept of individual value. If an item has extra value to a particular person, charging him that value would not violate Ona’ah. This applies when the person truly values the item more than its typical sale price. In contrast, a person that has no special affinity for the item and is forced to overpay out of desperation would be able to claim Ona’ah afterwards. See however Ktzos (227 (1)) that rejects this concept.

The prohibition against Ona’ah is when a seller overcharges, or a buyer underpays, for goods. In order to determine whether Ona’ah has been violated, it is critical to understand what the base ‘market price’ of an item is. Surprisingly, this is not discussed explicitly by the earlier Poskim- market price seems to have been considered a self-evident concept that required no further elaboration. However, in today’s fractured marketplace, it has become increasingly difficult to determine a precise market price. There are however, a number of rules to keep in mind:

1) Market price varies by geographical location- pricing in one city does not create a market price in another city. Each city has its own economic forces and an independent market, and vendors in one city are not bound to factor in the prices in another city. Presumably, an internet price cannot either be compared to pricing in a ‘brick and mortar’ location- there is typically a premium charged for the ability to see and feel the item and to be able to take your purchase home immediately. Thus, while the internet price will indirectly influence Ona’ah by effectively capping the price a store will be able to charge, it will not directly define the market price for a physical store.

2) Market price reflects the entire package of goods and services being sold. A purchase on credit may have a higher market price than a cash price; although the item is identical, the credit sale includes the benefit of a ‘loan’ which may be reflected in the higher price (subject to the laws of Ribbis). Similarly, a full service store may charge a premium over a ‘big box’ department store on account of the superior services that they offer. Another application would be the pricing from internet vendors that have differing customer ratings. A merchant that has better customer service and is more established is providing additional value, which may be reflected in the sale price.

3) Most goods today have a range of acceptable pricing. See Aruch Hashulchan 227 (7) that any price that is commonly found in the marketplace is considered a legitimate market value. Thus, if a particular good is widely sold by stores for either $50 or $60, either price would be considered acceptable. If however, a particular vendor charges above $60, or if a buyer pays below $50, Ona’ah would apply. In practice, this fact makes a claim of Ona’ah very difficult to prove. To the extent that a significant number of vendors sell the item at a particular price, there would be no claim of Ona’ah according to the Aruch Hashulchan even if the majority of vendors sell for a lower price. Thus, to prevail on a claim of Ona’ah, it is not enough to establish the average price for an item, but rather that the price paid is not an acceptable market price.

ללמוד: ויקרא כ"ה י"ד-י"ז, גמרא ב"מ נ"א ע"א 'מנה"מ', שו"ע רכ"ז א', סמ"ע א', קצות א'

ויקרא פרק כה

(יד) וְכִֽי־תִמְכְּר֤וּ מִמְכָּר֙ לַעֲמִיתֶ֔ךָ א֥וֹ קָנֹ֖ה מִיַּ֣ד עֲמִיתֶ֑ךָ אַל־תּוֹנ֖וּ אִ֥ישׁ אֶת־אָחִֽיו:

(טו) בְּמִסְפַּ֤ר שָׁנִים֙ אַחַ֣ר הַיּוֹבֵ֔ל תִּקְנֶ֖ה מֵאֵ֣ת עֲמִיתֶ֑ךָ בְּמִסְפַּ֥ר שְׁנֵֽי־תְבוּאֹ֖ת יִמְכָּר־לָֽךְ:

(טז) לְפִ֣י׀ רֹ֣ב הַשָּׁנִ֗ים תַּרְבֶּה֙ מִקְנָת֔וֹ וּלְפִי֙ מְעֹ֣ט הַשָּׁנִ֔ים תַּמְעִ֖יט מִקְנָת֑וֹ כִּ֚י מִסְפַּ֣ר תְּבוּאֹ֔ת ה֥וּא מֹכֵ֖ר לָֽךְ:

(יז) וְלֹ֤א תוֹנוּ֙ אִ֣ישׁ אֶת־עֲמִית֔וֹ וְיָרֵ֖אתָ מֵֽאֱלֹהֶ֑יךָ כִּ֛י אֲנִ֥י יְקֹוָ֖ק אֱלֹהֵיכֶֽם:

ספר החינוך מצוה שלז

שורש המצוה ידוע, כי הוא דבר שהשכל מעיד עליו, ואם לא נכתב דין הוא שיכתב, שאין ראוי לקחת ממון בני אדם דרך שקר ותרמית, אלא כל אחד יזכה בעמלו במה שיחננו האלהים בעולמו באמת וביושר. ולכל אחד ואחד יש בדבר הזה תועלת, כי כמו שהוא לא יונה אחרים גם אחרים לא יונו אותו, ואף כי יהיה אחד יודע לרמות יותר משאר בני אדם, אולי בניו לא יהיו כן וירמו אותם בני אדם, ונמצא שהדברים שוים לכל, ושהוא תועלת רב בישובו של עולם, והשם ברוך הוא לשבת יצרו.

בבא מציעא דף נא עמוד א

משנה. אחד הלוקח ואחד המוכר יש להן אונאה. כשם שאונאה להדיוט כך אונאה לתגר. ורבי יהודה אומר: אין אונאה לתגר. מי שהוטל עליו ידו על העליונה, רצה - אומר לו: תן לי מעותי, או תן לי מה שאניתני.

גמרא. מנהני מילי? דתנו רבנן: וכי תמכרו ממכר לעמיתך אל תונו. אין לי אלא שנתאנה לוקח, נתאנה מוכר מנין - תלמוד לומר או קנה אל תונו. ואיצטריך למכתב לוקח, ואיצטריך למכתב מוכר. דאי כתב רחמנא מוכר - משום דקים ליה בזבינתיה, אבל לוקח דלא קים ליה בזבינתיה - אימא לא אזהריה רחמנא בלא תונו. ואי כתב רחמנא לוקח - משום דקא קני, דאמרי אינשי: זבנית - קנית. אבל מוכר, דאבודי קא מוביד, דאמרי אינשי: זבין אוביד, אימא לא אזהריה רחמנא בלא תונו - צריכא.

שער שבשוק

ערוך השולחן חושן משפט סימן רכז סעיף ז

מדברי הרא"ש ז"ל יש ללמוד..... עוד נ"ל דבר אחד מדבריו לקולא במיני סחורות שאין כל בעלי חנויות מוכרין אותם בשוה שיש משתכר הרבה בסחורה זו ויש שמסתפק במועט אין שייך כלל אונאה למי שמשתכר הרבה כיון שדרך המסחר כן הוא כיון שיש שמוכרים במקחים כאלו דהא הרא"ש ז"ל לא תלה הספק אלא משום דלפעמים הלוקח חפץ במקח זה דאז יש סברא לאסור ומשמע להדיא דאין כאן מוכרין במקח כזה אבל כשיש מוכרין במקח כזה אין בזה צד אונאה ופשיטא שאין להביט על אותם החנונים המזלזלים במקחים ומוכרין בזול שמקלקלים לעצמם ומקלקלין דרכי המסחר והם ישאו עון וכבר אמרו חז"ל [ב"ב צ"א א] מתריעין על פרקמטיא שהוזלה ואפילו בשבת וכמ"ש באו"ח סי' תקע"ו: